posted August 04, 2013 04:43 AM

ORPHEUS

By (St.) Bernard EvslinHis father was a Thracian king; his mother, the Muse, Calliope. For awhile he lived on Parnassus with his mother and eight beautiful aunts and there met Apollo, who was courting the laughing Muse, Thalia. Apollo was taken with Orpheus and gave him a little lyre and taught him to play. And his mother taught him to make verses for singing.

So he grew up to be a poet and musician such as the world had never known. Fisherman used to coax him to go sailing with them early in the morning and had him play his lyre on the deck. They knew that the fish would come up from the depths of the sea to hear him and sit on their tails and listen as he played, making it easy to catch them. But they were not caught, for as soon as Orpheus began to play, the fisherman forgot all about their nets and sat on the deck and listened with their mouths open--just like the fish. And when he had finished, the fish dived, the fisherman awoke, and all was as before.

When he played in the fields, animals followed him, sheep and cows and goats. And not only the tame animals but the wild ones too--the shy deer, and wolves, and bears. They all followed him, streaming across the fields, following him, listening. When he sat down they would gather in a circle about him, listening. Nor did the bears and wolves think of eating the sheep until the music had stopped, and it was too late. And they went off growling to themselves about the chance they had missed.

And as he grew and practiced, he played more and more beautifully, so that now not only animals but trees followed him as he walked, wrenching themselves out of the earth and hobbling after him on their twisted roots. In Thrace now there are circles of trees that still stand listening.

People followed him too, of course, as he strolled about, playing and singing. Men and women, boys and girls--particularly girls. But as time passed and the faces changed he noticed that one face was always there. She was always there--in front, listening--when he played. She became especially noticeable because she began to appear among his other listeners, among the animals and the trees who listened as he played. So that finally he knew, that wherever he might be, wherever he might strike up his lyre and raise his voice in song, whether people were listening, or animals or trees or rocks--she would be there, very slender and still, with huge dark eyes and long black hair, her face like a rose.

Then one day he took her aside and spoke to her. Her name was Eurydice. She said she wanted to do nothing but be where he was, always; and that she knew she could not hope for him to love her, but that would not stop her from following him and serving him in any way she could. She would be happy to be his slave if he wanted her to.

Now, this is the kind of thing any man likes to hear in any age, especially a poet. And although Orpheus was admired by many women and could have had his choice, he decided that he must have this one, so much like a child still, with her broken murmurs and great slavish eyes. And so he married her.

They lived happily, very happily, for a year and a day. They lived in a little house near the river in a grove of trees that pressed close, and they were so happy they rarely left home. People began to wonder why Orpheus was never seen about, why his wonderful lyre was never heard. They began to gossip, as people do. Some said Orpheus was dead, killed by the jealous Apollo for playing so well. Others said he had fallen in love with a river nymph, had gone into the water after her, and now lived at the bottom of the river, coming up only at dawn to blow tunes on the reeds that grew thickly near the shore. And others said that he had married dangerously, that he lived with a sorceress, who with her enchantments made herself so beautiful that he was chained to her side and would not leave her even for a moment.

It was the last rumor that people chose to believe. Among them was a visitor--Aristeus, a young king of Athens, Apollo's son by the nymph Cyrene, and a mighty hunter. Aristeus decided that he must see this beautiful enchantress, and stationed himself in the grove of trees and watched the house. For two nights and two days he watched. Then finally he saw a girl come out. She made her way through the grove and went down the path toward the river. He followed. When he reached the river, he saw her there, taking off her tunic.

Without a word he charged toward her, crashing like a wild boar through the reeds. Eurydice looked up and saw a stranger hurtling toward her. She fled. Swiftly she ran...over the grass toward the trees. She heard him panting after her. She doubled back toward the river and ran, heedless of where she was going, wild to escape. And she stepped full on a nest of coiled and sleeping snakes, who awoke immediately and bit her leg in so many places that she was dead before she fell. And Aristeus, rushing up, found her lying in the reeds.

He left her body where he found it. There it lay until Orpheus, looking for her, came at dusk and saw her glimmering whitely like a fallen birch. By this time Hermes had come and gone, taking her soul with him to Tartarus. Orpheus stood looking down at her. He did not weep. He touched a string of his lyre once, absently, and it sobbed. But only once--he did not touch it again. He kept looking at her. She was pale and thin, her hair was disheveled, her legs streaked with mud. She seemed more childish than ever. He looked down at her dissatisfied with the way she looked, as he felt when he set a wrong word in a verse. She was wrong this way. She did not belong dead. He would have to correct it. He turned abruptly and set off across the field.

He entered Tartarus at the nearest place, a passage in the mountains called Avernus, and walked through a cold mist until he came to the river Styx. He saw shades waiting there to be ferried across, but not Eurydice. She must have crossed before. The ferry came back and put out its plank, and the shades went on board, each one reaching under his tongue for the penny to pay the fare. But the ferryman, Charon, huge and swart and scowling, stopped Orpheus when he tried to embark.

"Stand off!"� he cried. "Only the dead go here."

Orpheus touched his lyre and began to sing--a river song, a boat song, about streams running in the sunlight, and boys making twig boats, and then growing up to be young men who go in boats, and how they row down the river thrusting with powerful young arms, and what the water smells like in the morning when you are young, and the sound of oars dipping.

And Charon, listening, felt himself carried back to his own youth--to the time before he had been taken by Hades and put to work on the black river. And he was so lost in memory that the great sweep oar fell from his hand, and he stood there, dazed, tears streaming down his face--and Orpheus took up the oar and rowed across.

The shades filed of the ferry and through the gates of Tartarus. Orpheus followed them. Then he heard a hideous growling. An enormous dog with three heads, each one uglier than the next, slavered and snarled. It was the three-headed dog, Cerberus, who guarded the gates of Tartarus.

Orpheus unslung his lyre and played. He played a dog song, a hound song, a hunting song. In it was the faint far yapping of happy young hounds finding a fresh trail--dogs with one graceful head in the middle where it should be, dogs that run through the light and shade of the forest chasing stags and wolves, as dogs should do and are not forced to stand forever before dark gates, barking at ghosts.

Cerberus lay down and closed his six eyes, lolled his three tongues, and went to sleep to dream of the days when he had been a real dog, before he had been captured and changed and trained as a sentinel for the dead. Orpheus stepped over him and went through the gates.

Through the Field of Aspholdel he walked, playing. The shades twittered thin glee, like bats giggling. Sisyphus stopped pushing his stone, and the stone itself poised on the side of the hill to listen and did not fall back. Tantalus heard and stopped lunging his head at the water; the music laved his thirst. Minos and Rhadamanthys and Aeacus, the great judges of the dead, heard the music on their high benches and fell dreaming about the old days on Crete where they had been young princes, about the land battle and the sea battles and the white bulls and the beautiful maidens and the flashing swords, and all the days gone by. They sat there, listening, eyes blinded with tears, deaf to the litigants.

The Hades, king of the underworld, lord of the dead, knowing his great proceedings disrupted, waited sternly on his throne as Orpheus approached.

"No more cheap minstrel tricks,"� he cried. "I am a god. My rages are not to be assuaged, nor my decrees nullified. No one comes to Tartarus without being sent for. No one has before, and no one will again, when the tale is told of the torments I intend to put you to."

Orpheus touched his lyre and sang a song that conjured up a green field and a grove of trees and a slender girl painting flowers and all the light about her head, with the special clearness there was when the world had just begun. He sang of how that girl made a site so pleasing as she played with the flowers that the birds overhead gossiped of it, and the moles underground--until the word reached even gloomy Tartarus, where the dark king heard and went up to see for himself. Orpheus sang of that king seeing the girl for the first time in a great wash of early sunlight, and what he felt when he saw that stalk-slender child in her tunic and green shoes moving with her paintpot among the flowers; of the fever that ran in his blood when first he put his mighty arm about her waist, and drank her screams with his dark lips and tasted her tears; of the grief that had come upon him when he almost lost her again to her mother by Zeus's decree; and of the joy that filled him when he learned that she had eaten of the pomegranate.

Persephone was sitting at Hades' side. She began to cry. Hades looked at her. She leaned forward and whispered to him swiftly. The king turned to Orpheus. Hades did not weep, but no one had ever seen his eyes so brilliant.

"Your verse has affected my queen," he said. "Speak. We are disposed to hear. What is your wish?"

"My wife."

"What have we to do with your wife?"

"She is here her name is Eurydice. I wish to take her back with me."

"Never done,"� said Hades. "A disastrous precedent."

"Not so, great Hades,"� said Orpheus. "This one stoke of unique mercy will illumine like a lightning flash the caverns of your dread decree. Nature exists by proportion, and perceptions work by contrast, and the gods themselves are part of nature. This brilliant act of kindness, I say, will make cruelty seem like justice for all the rest of time. Pray give me back my wife again, great monarch. For I will not leave without her--not for all the torments that can be devised."

He touched his lyre once again, and the Eumenides, hearing the music, flew in on their hooked wings, their brass claws tinkling like bells, and poised in the air above Hades' throne. The terrible hags cooed like doves, saying, "Just this once, Hades. Let him have her. Let her go."

Hades stood up them, black-caped and towering. He looked down at Orpheus and said, "I must leave the laurel leaves and the loud celebrations to my bright nephew Apollo. But I, even I, of such dour repute, can be touched by eloquence. Especially when it attracts such unlikely advocates. Hear me then, Orpheus. You may have your wife. She will be given into your care, and you will conduct her yourself from Tartarus to the upper light. But if during your journey, you look back once, only once...if for any reason whatever you turn your eyes from where you are headed and look back to where you were...then my leniency is revoked, and Eurydice will be taken from you again, and forever. Go!"

Orpheus bowed, once to Hades, once to Persephone, lifted his head and smiled a half-smile at the hovering Furies, turned and walked away. Hades gestured. And as Orpheus walked through the fields of Tartarus, Eurydice fell into step behind him. He did not see her. He thought she was there, he was sure she was there. He thought he could hear her footfall, but the black grass was thick; he could not be sure. But he thought he recognized her breathing...that faint sipping of breath he had heard so many nights near his ear; he thought he heard her breathing, but the air again was full of the howls of the tormented, and he could not be sure.

But Hades had given his word; he had to believe...and so he visualized the girl behind him, following him as he led. And he walked steadily, through the gates of Tartarus. The gates opened as he approached. Cerberus was still asleep in the middle of the road. He stepped over him. Surely he could hear her now, walking behind him. But he could not turn around to see, and he could not be sure because of the cry of the vultures which hung in the air above the river Styx like gulls over a bay. Then, on the gangplank, he heard a footfall behind him, surely...why, oh why, did she walk so lightly? Something he had always loved, but he wish her heavier-footed now.

He went to the bow of the boat and gazed sternly ahead, clenching his teeth, and tensing his neck until it became a thick halter of muscle so that he could not turn his head. On the other side, climbing toward the passage of Avernus, the air was full of the roaring of the great cataracts that fell chasm-deep toward Styx, and he could not hear her walking and he could not hear her breathing. But he kept a picture of her in his mind, walking behind him, her face growing more and more vivid with excitement as she approached the upper air. Then finally he saw a blade of light cutting the gloom, and he knew that it was the sun falling through the narrow crevasse which is Avernus, and that he had brought Eurydice back to earth.

But had he? How did he know she was there? How did he know that this was not all a trick of Hades? Who calls the gods to judgment? Who can accuse them if they lie? Would Hades, implacable Hades, who had the great Asclepius murdered for pulling a patient back from death, would that powerful thwarting mind that had imagined the terrain of Tartarus and the bolts of those gates and dreamed a three-headed dog--could such a mind be turned to mercy by a few notes of music, a few tears? Would he who made the water shrink always from the thirst of Tantalus and who toyed with Sisyphus's stone, rolling it always back and forth--could this will, this black ever-curdling rage, this dire fancy, relent and let a girl return to her husband just because the husband asked? Had it been she following him through the Field of Asphodel, through the paths of Tartarus, through the gates, over the river? Had it been she or the echoes of his own fancy--that cheating mourner's fancy, which, kind but to be cruel, conjures up the beloved face and voice only to scatter them like smoke? Was it this, then? Was this the final cruelty? Was this the torment Hades had promised? Was this the final ironic flourish of death's scepter, which had always liked to cudgel poets? Had he come back without her? Was it all for nothing? Or was she there? Was she there?

Swiftly he turned, and looked back. She was there. It was she. He reached his hand to take her and draw her out into the light--but the hand turned to smoke. The arm turned to smoke. The body became mist, a spout of mist. And the face melted. The last to go was the mouth with its smile of welcome. Then it melted. The bright vapor blew away in the fresh current of air that blew through the crevasse from the upper world.

*****************************************

MYTHOLOGY BECOMES LANGUAGE

ORACLE is derived from the Greek word meaning "to pray."� It is used to refer to places where people pray: oratories; to great speakers: orators; and even great speeches: orations. A person who seems to possess great knowledge or intuition is called an oracle, and his statements are described as oracular.

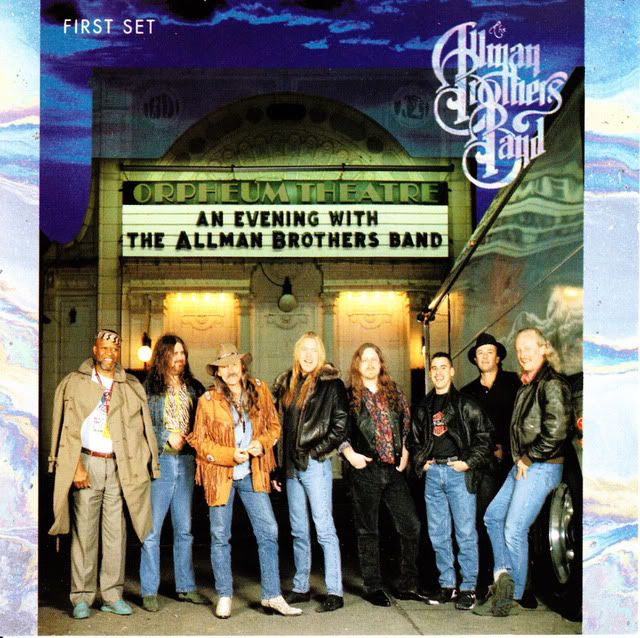

ORPHEUM refers to Orpheus, the sweetest singer to ever sing. This term is used by many theaters and places of entertainment.

CALLIOPE is the name of a musical instrument. The mother of Orpheus was named Calliope because she was the Muse of Eloquence and Heroic Poetry. The name comes from two words meaning "beauty"� and "voice."�

MUSES refers to the nine goddesses of dancing, poetry, and astronomy. We use the verb muse to describe the act of pondering or meditating. The words music, musician, and musical all come from this word.

************************************

ORPHIC

adj. 1. Greek Mythology Of or ascribed to Orpheus: the Orphic poems; Orphic mysteries. 2. Of, relating to, or characteristic of the dogmas, mysteries, and philosophical principles set forth in the poems ascribed to Orpheus. 3. Capable of casting a charm or spell; entrancing. 4. Often orphic Mystic or occult.

ORPHISM

n. 1. An ancient Greek mystery religion arising in the sixth century B.C. from a synthesis of pre-Hellenic beliefs with the Thracian cult of Zagreus and soon becoming mingled with the Eleusinian mysteries and the doctrines of Pythagoras. 2. Often orphism A short-lived movement in early 20th-century painting, derived from cubism but marked by a lyrical style and the use of bold color.

UNDERWORLD

n. 1. The part of society that is engaged in and organized for the purpose of crime and vice. 2. A region, realm, or dwelling place conceived to be below the surface of the earth. 3. The opposite side of the earth; the antipodes. 4. Greek Mythology Roman Mythology The world of the dead, located below the world of the living; Hades. 5. Archaic The world beneath the heavens; the earth.

LOve  & LIght

& LIght  ,

,

Stephanie

_________________________

Got the Wings of Heaven on my shoes. I'm a dancin' man and I just can't lose. You know it's all right, it's okay. I'll live to see another day. We can try to understand. The New York Times' effect on man. Whether you're a brother or whether you're a mother. You're stayin' alive, stayin' alive.

Stayin' Alive ~ The Bee Gees

Lindaland

Lindaland

The OOber Galaxy

The OOber Galaxy

silly question (Page 1)

silly question (Page 1)